Usisikie tetesi, mi ni nuksi

Don’t listen to the rumour, I am dangerous

Nakwenda upesi upesi, kisha nakwenda pole pole bila kelele

I am going swiftly, and then slowly without a sound

Mpaka kwenye kilele, mi ni Nyerere wa rap

To the top, I am the Nyerere of rap

II Proud([2]) in: ‘Moja Kwa Moja’

This paper is based on the fieldwork experiences of the authors between June 1997 and January relating to hip hop culture in Tanzania. Fieldwork was done in the urban context of Dar es Salaam, Arusha and Zanzibar town. Interviews were conducted in English and Kiswahili. One of the most striking elements of Tanzanian hip hop is Kiswahili-rap, and the Kiswahili rap audience is predominantly a young one. Furthermore, in Tanzania the association of youth culture to music is virtually limited to one genre: rap. In a country where about half the population is younger than fifteen, this means the influence of the music is vast. As far as other musical genres go, reggae music is still listened to but in Dar es Salaam has a relatively limited audience and popularity amongst the youth when viewed in relation to hip hop. Before rap became popular, reggae music was the transnational ‘commoditized’ music to make an impact on Tanzania’s youth([3]). Bob Marley was generally held to be the hero of the youth.

Another genre, Congolese music, or ‘bolingo’ as this music is called in Tanzania, is also still very popular. Nonetheless, young hip hop fans generally see it as music for older people. At present there has not been much written about Kiswahili rap([4]), despite the fact that in Tanzania the genre has existed since about 1991. Therefore it can be argued that scientific attention and research relating to this important phenomenon in Tanzanian cultural production is long overdue. The aim of this article is to provide the reader with insight regarding the Kiswahili rap genre, focusing especially on the genre’s history and its competitive elements.

In order to get an idea of the circumstances within which Kiswahili rap developed it is necessary to address the recent social and economic changes that have taken place in urban Tanzanian society. To say the least, Tanzanian society is changing fast. Since 1985, when president Nyerere gave power to Ali Hassan Mwinyi, Tanzania’s economy has been carefully liberalized, resulting in more political freedom. In 1992 a multi party system was introduced, thus giving a legitimate voice to the opposition. In 1995 president Mkapa was elected president, and further liberalized the economy. As a result, since 1995 the urban landscape of Dar es Salaam has dramatically changed. For example, the mobile phone has become a status symbol of some importance. State owned buses are rare and the privately owned daladala services dominate the streets. On the pavement of the city center the wamachinga([5]) spread their trade. Since 1993 their numbers have doubled and are increasing by more than 5,000 every month. The number of newspapers and magazines for offer are dazzling. Sources([6]) from 1997 indicated there are 92 newspapers and magazines published in Dar es Salaam alone. However during our fieldwork we experienced the addition of a new newspaper to this expanding market almost every week.

Under the leadership of president Mkapa, from 1995 on there has been much more openness (Uwazi) in Tanzania. Before this, ‘mwalimu’ Nyerere always emphasized the country’s self-reliance. At his time there was not much ‘foreign’ music heard on the radio (with the exception of Congolese music) and the media were under state control. Prior to 1995 Tanzania had no t.v. stations except for the sole state owned TVZ (Zanzibar). At present Tanzania is blessed with four more television stations (ITV, DTV, CTN and CEN) and more than a hundred dailies, (bi-)weeklies and monthlies. The choices are dazzling. A great deal of American rap music is broadcast on radio and television daily.

Before the period of liberalization and privatization outlined bove, the rap music genre reached a limited number of individuals in Tanzania who had special contacts with friends or family outside the country. Now one can find rap on every streetcorner and in every home with a television, as ‘global’ culture enters the lives of the Tanzanian people in ever greater quantities, bringing with it the new and rapidly evolving musical genres of the western world. It comes as no surprise that there is a correlation between the rise of Kiswahili rap and the liberalization of the economy from 1985 onwards, and this is reflected in the attitude of the genre’s local artists, who speak favorably of the changes which have increased their artistic freedom:

Mimi ni Dolla Soul kutoka De-Plow-Matz nasema ruksa!

I am Dolla Soul from Tha De-Plow-Matz, I am saying; go ahead.

Kufanya unachotaka, Bongo([7]) uwazi.

To do anything you want, Tanzania is open.

Na ukweli si uongo ndani ya Bongo, tumia ubongo.

And the truth is not a lie in Tanzania, use your intelligence.

Dola Soul (De-Plow-Matz) on the cassette: ‘Ndani ya Bongo’ by II Proud (1997)

The openness (Uwazi) mentioned here is contributing to a new mode of living for many Tanzanian people. In reality this new life boils down to a struggle for survival in the city, where many people from different backgrounds are forced by physical circumstance to find a common ground. In some sense one could argue that a new moral community is being created. This community is deeply rooted in Tanzanian culture but new elements and ideas are being incorporated in reaction to the changing political and economic landscape. For the young generation rap music plays a pivotal role in this process of transculturation([8]). This can be confusing for the generation that was brought up with Nyerere’s politics. Although Nyerere is still widely respected by young and old, his agriculturally focused brand of socialism is fading in popularity as the city with all its rewards and dangers continues to lure people from the countryside into the already crowded streets of Dar. Unemployment is rising at an alarming rate, and theft is a growing problem. Many people blame the influence of ‘foreign culture’. This example is taken from a newspaper article:

The openness (Uwazi) mentioned here is contributing to a new mode of living for many Tanzanian people. In reality this new life boils down to a struggle for survival in the city, where many people from different backgrounds are forced by physical circumstance to find a common ground. In some sense one could argue that a new moral community is being created. This community is deeply rooted in Tanzanian culture but new elements and ideas are being incorporated in reaction to the changing political and economic landscape. For the young generation rap music plays a pivotal role in this process of transculturation([8]). This can be confusing for the generation that was brought up with Nyerere’s politics. Although Nyerere is still widely respected by young and old, his agriculturally focused brand of socialism is fading in popularity as the city with all its rewards and dangers continues to lure people from the countryside into the already crowded streets of Dar. Unemployment is rising at an alarming rate, and theft is a growing problem. Many people blame the influence of ‘foreign culture’. This example is taken from a newspaper article:

[…] The videos have brought into this country so many cultures it scares the hell out of me. There are so many cultures the city is losing direction. Just the other day I found a toddler singing raggamuffin in Swahili. Ha ha ha… It is as if we do not have an African culture. What a shame! One day an African elder asked me: John, say, and what is this thing they call ‘kula midenda!'([9]) It is definitely copied from videos this love culture. […]([10])

The emphasis on cultures is ours. It is interesting to see the writer’s essentialist definition of culture. The writer of the cited article is not alone in his opinion. When we tried to buy some Kiswahili rap near Kariakoo market the shop owner asked us: ‘Why are you interested in this music? These kids are spoiling our culture, they want to be Americans!’. Another journalist in Dimba went so far as to accuse rap music of making youngsters leave school and become criminals([11]). His argument was paralleled by his belief that the American heavy metal group ‘Megadeath’ are devil worshippers. The writers leave it to the reader to try to find the connection between Tanzanian rap artists and Megadeath and their songs. It suffices to say that essentialist arguments against globalization processes are to be found in many countries facing similar patterns of transculturation as those witnessed over the course of Tanzanian economic liberalization. Kiswahili rap artists are used to these sorts of media reports. The press has mushroomed in size since 1995 and there is little control of the content of articles published . In this way many Kiswahili rap albums have been reported to be released or in circulation, even though the albums do not even exist.

The early days of Kiswahili rap have yet to be documented. Reconstructing the past is often not an easy task and every Tanzanian rap-artist has his or her own story to tell. Here we examine the story as it is told by KBC, a member of the Kwanza Unit from Dar es Salaam. His story serves as a good example of the ways in which Kiswahili hip hop culture is acted out. Rap music has been popular in Tanzania ever since the first American rap records appeared, even if distribution was poor and local production non-existant. In the early eighties transnational connections proved to be effective in terms of introducing the genre. Reflecting this state of affairs, in these early days many Tanzanian rap artists either copied the lyrics of American rap artists or wrote in English. No one thought it possible to write a Kiswahili rap.

However, in the early nineties this was to change. KBC tells the story of a cultural evening that was being organized in 1991 at the International School of Tanganyika in Masaki, Dar es Salaam.([12]). Anyone could take part but the theme of the pieces had to be linked to Tanzanian culture. Most students presented traditional dance performances but two brothers, Big X and Cool Mo’ C, wanted to rap. In order to stay with the theme of the evening they decided to write a rap in Kiswahili about AIDS and safe sex. This event can be viewed as an important moment in the progression of Kiswahili rap due to the fact that not long after most Tanzanian rap fans were making efforts to write rap in Kiswahili. Hence the importance KBC places upon this event relates to marking the moment at which local language rap production began in ernest. The first Kiswahili rap cassette which found its way to the shops was Saleh J’s ‘Ice Ice Baby’, released in 1991. Saleh’s lyrics were basically a translation from English to Kiswahili of American rap hits.

At this time KBC had already been rapping, while he was in secondary school. One of his school friends worked as a DJ playing at parties. He called himself the ‘Young Millionaire’, since he was wealthy for someone of his age, more affluent than his peers. According to KBC ‘[he] had nothing to do with it [the money] but to have fun’. At that time Young Millionaire would boast that he was known and KBC was not. KBC for his part, continued to socialize, doing freestyle raps with his clique called Rapport. According to KBC, he became popular because he would mention the names of his friends in his raps. For the moment he was simply doing it for the love of it: ‘It was not about the money but about earning respect and representing’. Unaware that he was developing his rap skills to a more professional level, he admired another rap-artist called Fresh XC. Whenever that rapper was at a party, KBC refused to ‘take the mic’ because he did not think that his talents were adequate. One day, as usual, KBC went to one of the hip hop parties, wearing a brand new ‘Run DMC’ tracksuit which his mother had just brought from the US. He was closely following Fresh XC and Young Millionaire when one particular rap was being performed and a chorus was raised by some of his friends who wanted him to perform. KBC ‘didn’t have time to think’ and he ‘bust off’ into a freestyle piece which was loved by the crowd. ‘From that day I earned my respect.’

The early Kiswahili rap, unlike today’s repertoire, did not reach its audience through radio, tv and cassettes, but mainly through live performances. In the early nineties, the yearly ‘Yo Rap Bonanza’ rap competitions organized by Kim & the Boyz Promotion in Dar’s New Africa Hotel attracted large crowds. Rapper II Proud who at the time was present as a spectator recalls:

‘In those days you asked the deejay [for an instrumental], nobody had instrumentals that day. So you just go to the deejay, you ask ‘You have certain instrumental of Heavy D? Yes I have. You have certain instrumental of Naughty by Nature? No I don’t have, choose another – it was like that. There was a master of ceremony, and the mc says ‘Now it’s time for mc II Proud’. [¼.] Mc’s used pre-written lyrics. The organisers used to say ‘This year’s competition we are going to choose lyrics talking about how drugs are bad for youth’, so everybody was writing about. [¼] After giving the message, at the outtro mc’s started saying ‘Yo, this is the man, so-and-so, all you mc’s in the house yo fuck y’all you don’t know how to do it, I am the man and I represent. I’m like Ice Cube, and so on.'([13])

The days of Yo Rap Bonanza are over. Now and then a talent show is organised and a winner is announced, but usually this doesn’t get much attention. Competition has moved on to new fields.

When compared to other Tanzanian musical genres, Kiswahili rap seems to outdo all in the fierceness of its competitive content. Rappers are aware of competition in other styles of music. As II Proud says when illustrating the case of Diamond Sound versus FM Musica (a Dar es Salaam bands competition which was taking place from 1997 on): ‘as long as there are bands there is business, so there will be competition’. But rather than just being the consequence of the fight for prominence and the new market, the competitive element of rap also seems to have artistic value which has been a part of hip hop culture since the earliest days of its existence. As David Toop points out, American rap, in its form of a rapper performing on stage with a deejay, first appeared in the Bronx, New York during the mid-seventies, and took a large part([14]) of its inspiration from Afro-American oral traditions. Citing Roger Abrahams who wrote on Afro-American oral literature of Camingerly, Philadelphia in the 1950’s:

‘Verbal contest accounts for a large portion of the talk between members of this group. Proverbs, turns of phrases, jokes, almost any manner of discourse is used, not for purposes of discursive communication but as weapons in verbal battle. Any gathering of the men customarily turns into ‘sounding’, a teasing or boasting session’ ([15])

These practices lived on in the rap jams that took place all over New York in the late seventies and found their way onto vinyl when the first rap records came out in 1979. At the time it was a Jamaican immmigrant named DJ Kool Herc who took the Jamaican concept of a sound system and introduced it to New York. He started throwing parties where he would invite another deejay to compete against his setup which consisted of two turntables, a disco mixer, an amplifier and huge speakers([16]). The role of the ‘mc’ (master of ceremony) was to comment on the work of the opponents who were located at the other end of the hall, each trying to attract the crowd by means of superior music and performance. Rapping over a beat provided by the deejay looping two copies of one record, the raps made fun of the sound system at the other side. The mc’s sometimes borrowed from Afro-American oral traditions literally, such as in the case of ‘Yo mama’-jokes which describe someone’s mother in a humiliating way. This practice was to live on in hip hop recordings throughout the eighties and nineties, further developing the self-glorifying qualities of the mc in various identities (pimp, gangster, ladykiller etc.). When videos became an important aspect of record sales strategy (as a result of the growing popularity worldwide of music television such as MTV), video clips added a new dimension to the boasting element in hip hop. Rappers could be seen in expensive suits or with gold chains, driving expensive cars while rapping about their lyrical prowess. The boasting in rap has been a point of discussion both within and outside the hip hop audience. As we will see further on, the enactment of a high society or ‘larger than life’ style which has reached new heights in today’s American rap and r&b has in itself become the focus of a debate in which rappers accuse each other of not being true to their origins, and so ‘realness’ has become a competitive element. In Tanzania from the mid-eighties onwards these developments in American rap music have been followed by local rappers and are reflected in a local variety of highly competitive rap music.

As in any hip hop market, competition in Kiswahili rap takes place on several levels. One of the major ways in which mc’s can express their superiority over their opponents has always been the delivery of their rhymes. This has been the case in Tanzania as well, ever since the ‘Yo Rap Bonanza’ competitions held in the late eighties. An important way for a group or mc to get the attention of the audience was and is to come up with a unique style of rapping (‘flow’, or ‘mtiririko’). Most Tanzanian rap fans easily distinguish a newcomer from a veteran rapper by judging the fluency of his rap. Groups or solo artists that came up with their own new rap style (often combined with a unique choice of words) are picked up by the audience. A good example is Gangsters With Matatizo (G.W.M.) whose song ‘Cheza Mbali na Kasheshe’ (Stay Away from Trouble), a highly original composition in a refreshing rap style, was adopted by Radio One and subsequently became a national rap anthem for months after its release in 1996.

Still the flow alone has never been enough to grab the lasting attention of the listeners. The style of delivery alone is not enouth, in Tanzania the hip hop audience is carefully listening to the words. Lyrics are judged by the hip hop concept of ‘keeping it real’ which was originally introduced into American hip hop around 1995 as a reaction to the ongoing ‘commercialisation’ of rap music. American hip hop music is closely followed by Tanzanian rap fans, but the situation in the U.S.A. is different from the one in Tanzania. In America rap music has become a multi-million dollar business as evident from the scale of video and album production. Also the level of violence in American society is recognized as being a central source of difference. Rap artists in Tanzania who are trying to copy the content of American rap are criticized. An interesting example of this was captured while recording an English language rap in the streets. The rap artist started rapping about how he was driving in his Lexus([17]). His friend, rapper Abbas from the group Underground Souls, suddenly grabbed the mic and told him off:

‘Yo, you’re saying yourself that […] ‘I was riding in the Lexus, driving Mercedes, know what I’m saying, and I got a VCR’. That was really…fuck yours! Even though you’re putting these things in the rhymes and in the video, even though you can’t afford it [….] That is not keeping it real! We don’t afford Lexus, we don’t afford using guns. In Tanzania we [are a] peace country. We don’t use guns.’

A similar attitude of difference is expressed towards the use of abuse (‘matusi’) in rap performances. While it is obvious that Radio One won’t play any records that contain curses, the audience is just as critical during live performances, booing the mc off stage if he would dare to call somebody a ‘motherfucker’ with the words ‘You must be talking about your own mother!'([18])

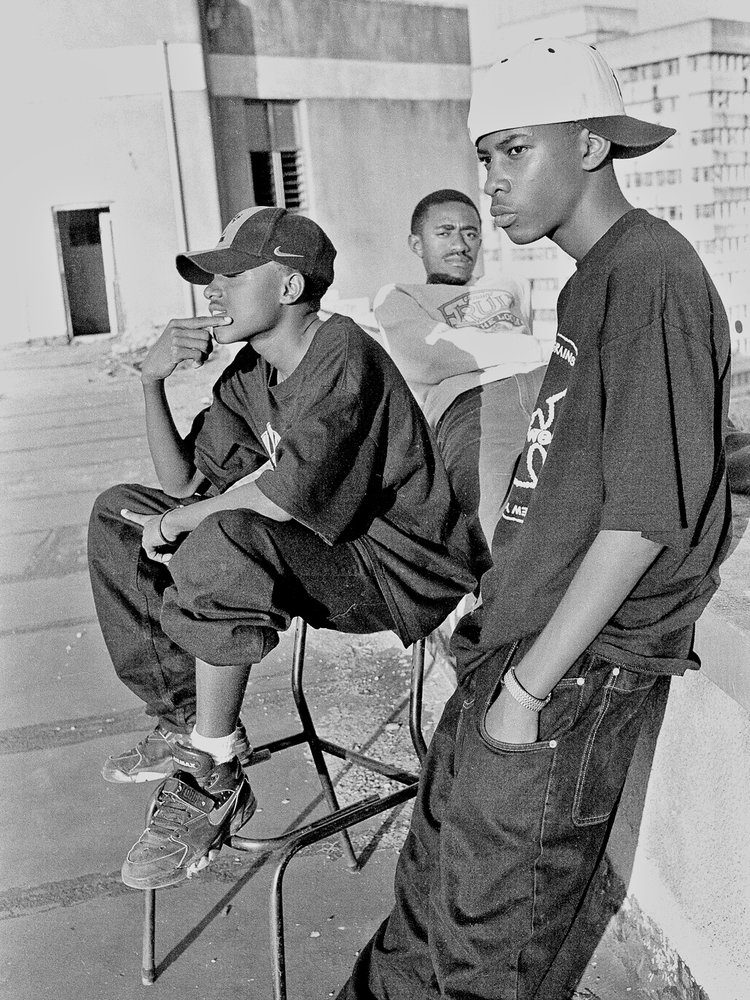

This competition for status is not limited to rap alone, either. Material culture is flourishing in Tanzania, and among most hip hop fans it is important to wear the right gear. If you can afford to wear Nike trainers, which in Tanzania sell for at least three times the price one would pay in the U.S.A., and a Wu-Tang T-shirt, you are seen as well off. This is not only important for recognition by peer groups but also an advantage in communication between the opposite sexes. To go deeper into material culture would be an interesting topic for further research. When discussing the competitive nature of Tanzanian hip hop culture the importance of photography should not be underestimated. Every important event is photographed, because this is ‘evidence’ that it really happened.

In Dar es Salaam there are a few venues which are well known for being spots where dress is of special importance. Whereas Zairean music in Dar es Salaam has its regular dress and dance competitions, held in such places as Friends Corner in Manzese, hip hop fashion has remained without official prize winning events. However in discos like the recently opened Bilicanas in the city centre, or the Poolside disco at Kilimanjaro hotel([19]), the gaze of the audience is felt. Another venue that has become popular with the Dar es Salaam rap audience is Coco Beach, a beach club towards Masaki where every sunday hundreds of people from town come to walk along the beach until sunset. The full social spectrum of Tanzanian hip hop culture is displayed by such a gathering spot. At Coco Beach, rap concerts have been organised regularly. Rappers and those with a liking for hip hop gear are sure to be there decked out in their latest goods. The more well-off come in four wheel drive vehicles which are equipped with 200 Watt stereos blasting hip hop or r&b music. Others hold motor races which are watched by the crowd sitting in the back of their cars. The gathering seems to be modelled on beach parties which appear in American hip hop movies such as ‘Phat Beach’, pirated video copies of which sell all over Tanzania for the equivalent of $3 US. The image of youth gathering on the beach in the latest gear and equipped with sound systems is also portrayed in the very popular Kiswahili comics such as ‘Bongo’, ‘Tabasamu’ and ‘Sani’ and in the opening scenes of ‘Kifo cha 2Pac’, a Kiswahili comic relating the story of the American rapper 2Pac whose gangster style murder deeply shocked Tanzania’s rap audience.

Another level on which rappers compete is that of knowledge relating to what is perceived by some as ‘the’ hip hop culture. There is an ongoing debate within American rap about the definition of hip hop culture. When looking for a definition, many times the same answers are found repeatedly, from one hip hop community to another. Hip hop is claimed to be a universal culture, crossing territorial lines, thus enabling people in, for example, Japan, Holland, France and South Africa to discuss topics that concern all of them as members of a larger transnational hip hop culture. Also many people (both in rap songs and in discussion, see ‘letters’ pages in hip hop magazines such as Rap Pages) see hip hop culture as a trinity consisting of rapping, breakdancing and doing graffiti art. While this definition is essentially urban, it does connect hip hop culture in different countries and languages. Furthermore, hip hop has its own myths of origin which are as unclear and shrouded in clouds as the origins of Tanzanian rap. Nonetheless, in almost all of the places to which hip hop culture has spread, the Bronx in New York is cited as its place of birth. Even rap fans in the more remote parts of Tanzania and those who do not understand English have an idea of where rap originated.

In Tanzania knowledge about the early days of rap is not possessed by all those who practise rap. Whereas rap songs tend to function as carriers of the basic values that underly hip hop, its history and background cannot easily be understood from lyrics alone. In America and Europe books on hip hop such as the classic ‘Rap Attack’ by David Toop, magazines such as Source, Vibe, and HHC, video documentaries and movies such as Wildstyle from 1982 function as major sources of information for those who wish to learn about the origins of hip hop. In Tanzania, all of these items are barely available, if at all. Therefore access to this information has become a source of competition, despite the fact that knowledge of American hip hop slang is possessed by only a few Tanzanian rappers. The language barrier makes it near to impossible for most of the Tanzanian rap audience to understand what rappers are talking about, not to mention the difficulty of producing texts in English with a similar richness of metaphor and slang expression as that of the American rappers. Those who do take hold of the American hip hop slang and are able to use it in their own rhymes, do so with pride. Their understanding of the rhyming structures of American rappers extends to their Kiswahili rhymes. Here it is useful to take the example of the Kwanza Unit.

The Kwanza Unit have been among the first rap-crews of Tanzania and almost all the core members maintain good connections with friends and family living outside Tanzania. In this way they have secured fairly easy access to hip hop magazines and video tapes. They have also been rapping since what they refer to as the early days of hip hop, that is to say from the late eighties. They have a good knowledge about hip hop in general and are constantly boasting about it:

KBC: […] The K.U. Crew basically means the Kwanza Unit. On the other hand it means Knowledge Universal, if you slipped on that…Knowledge Universal. […]

Abbas (in the background): Let me kick a verse..

KBC: Nah, don’t kick a verse. I’m busting out knowledge!

When KBC starts explaining about ‘this hip hop thing’, it becomes clear that he considers himself to be something of an expert on hip hop history. As already mentioned KBC is a member of the Kwanza Unit. They are the largest and one of the oldest crews in Tanzania. The Kwanza Unit is made up of different youth groups that dominated the Dar es Salaam hip hop scene in the late eighties. These groups, ‘posses’ or ‘cliques’ as they are commonly referred to, were not yet rapping but they socialized together, listened to and talked about music, practised break-dancing, did some graffiti and ‘dissed’ rappers for fun. The groups would sometimes meet at the discos and other places of entertainment and occasionally fights would start because of the size of the group. When two or three of the groups decided to unite within the Kwanza Unit, it was generally seen as a peace-truce. Only then did the Kwanza start to rap on a more serious or professional level. One of its founding members, Rhymson, was hired by ITV (Independent Televison), making it possible for the group to record a number of video clips. They were also able to produce two albums, though these were not distributed due to financial and organisational difficulties. The management of a group as large as the Kwanza Unit proved to be extremely cumbersome, especially in a city where telecommunication is problematic. Due to this problem usually only half of ‘the crew’ turns up for concerts.

The Kwanza Unit gained their popularity in the early days of Kiswahili rap mainly because they were the biggest and most active rap group. The Unit itself consisted of no less than fifteen members while the extended Kwanza Family or the K.U. Foundation had hundreds of members. To be a member of the Kwanza Unit crew or family one had to be ‘down’ with the K.U. ‘Philosophy’ of hip hop. Either you were included or excluded. Not everyone was able to fit into their rather narrow definition of hip hop which focused on the New York variety. Out of this, one of the more serious arguments in the history of Tanzanian rap developed.

In 1995 a radio station held a contest during which listeners were asked to phone in and vote for either the Kwanza Unit or the De-Plow-Matz in order to elect ‘the most popular rap crew’.([20]) The De-Plow-Matz were the younger of the two groups and still at secondary school, interested mostly in the west coast style of American rap. Hundreds of school friends phoned in and as a result the De-Plow-Matz were elected the most popular rap crew. The Kwanza Unit saw their position endangered and stopped greeting De-Plow-Matz members in the street. Saigon of De-Plow-Matz and SOS B recorded a song called Msuli, which did not help in calming the situation for its chorus was:

In 1995 a radio station held a contest during which listeners were asked to phone in and vote for either the Kwanza Unit or the De-Plow-Matz in order to elect ‘the most popular rap crew’.([20]) The De-Plow-Matz were the younger of the two groups and still at secondary school, interested mostly in the west coast style of American rap. Hundreds of school friends phoned in and as a result the De-Plow-Matz were elected the most popular rap crew. The Kwanza Unit saw their position endangered and stopped greeting De-Plow-Matz members in the street. Saigon of De-Plow-Matz and SOS B recorded a song called Msuli, which did not help in calming the situation for its chorus was:

Vyovyote utakavyo, wee utacheza msuli

Anyhow you like it, you will play the muscle

Haya njoo ufe -njoo, njoo!

Hey, come you die -come come!

Nasema njoo ufe -njoo njoo ufe!

I say come you die -come come you die!

From: ‘Msuli’ (unreleased)

The song was partly a response to a freestyle([21]) which the Kwanza Unit performed, in which they ‘dissed’ (disrespected) the De-Plow-Matz. The Kwanza Unit saw the lyrics of Msuli as a personal insult to their talents and abilities and so tried to record a reply, however their producer Master Jay refused to record the song. Thus the ‘beef’ ended. A great deal of time passed before Kwanza Unit and De-Plow-Matz returned to speaking terms, and even now the echoes of the argument are still felt, although in the summer of 1997 people on the Tanzanian hip hop scene basically recognized the need to work together rather than avoiding each other.

The local rivalry between the K.U. and the De-Plow-Matz is discussed mainly in terms of musical styles. Hip hop music was first performed in New York, on the American East coast, and is therefore seen by some as the true hip hop. American West coast rappers are criticized for not doing ‘real’ hip hop as in recent years some of them embraced a ‘living large’ identity which is echoed in their lyrics and depicted in their videos. There is also a general difference in musical style between the two areas, and a long history of conflict carried out in the form of ridicule, or ‘dissing’. The fact that Tanzania is located on the African east coast gives this territorial competition an extra dimension. Recently when rap artists 2 Pac (from the American west coast) and Notorious B.I.G. (east coast) were killed, the differences of styles were used by some in the hip hop/rap debate. The deaths of 2 Pac and B.I.G. fueled much media attention in Tanzania and were still being discussed during the summer of 97.

Arguments such as the one described above are common in Tanzanian rap. Still, most rap artists agree that in order to strengthen their position within the Tanzanian music business they will have to form alliances. Recently solo artist II Proud and the De-Plow-Matz have strengthened their ties, each appearing on the other’s albums as well as performing together. The rap crew ‘The Hardblasters’ is even trying to form a Party of Rap (CCR, short for Chama Cha Rap). They have written a manifesto (Katiba ya Chama Cha Rap) in which they explain their goals, a few of which are: to unite all Tanzanian rap artists under one body, to promote relationships between rappers in Tanzania and hip hop culture in other parts of the globe, and to help rappers selling their products on the local market. However, other rap artists are sceptical, either they don’t believe it can work out or they are afraid that the Hardblasters will use the organization only to promote their own career.

In the above we have seen that in the tradition of rap music, which introduced some practices originating in Afro-American oral literature to Tanzanian youth, competition plays an important role. In the performance of Kiswahili rap in Tanzania the various levels of competition in American hip hop have been interpreted and reflected. This has occurred alongside existing Tanzanian practices such as the Yo Rap Bonanza competitions. As the influx of American rap music into Tanzania has increased considerably since the late eighties, so the use in local rap of competitive elements originating in the Bronx and indicative of the larger American hip hop scene in general has become more wide-spread. However, access to knowledge of American hip hop is not easily available to everybody and therefore is still a source of competition and division. In this way even the practice of competing in itself (e.g. freestyling) has become an element which is used by some to stress their superiority ‘in the game’, as opposed to those Kiswahili rappers who do not take part in such competitive interpretations of hip hop culture.

Selected discography

Only a few Kiswahili rap albums are widely available in Tanzania. Most studio recordings are never commercially released. The usual procedure for getting a rapper’s new songs through to a larger audience is by personally handing over cassette copies to radio deejays. Radio Tanzania is available all over the country and the Dar-based Radio One has expanded its broadcasting to other regions such as Arusha and Mwanza. In this way even rural communities are well informed of the latest developments on the Dar es Salaam music scene, as the authors found out when attending a disco in Sukuro in the heart of the Maasai Steppe, where children were chanting the ‘Ekibinda Nkoi’ chorus from the latest Diamond Sound hits. The market for Kiswahili rap cassettes has developed all over Tanzania, as the countrywide sales of II Proud’s second album (officially up to 10000 cassettes have been sold but unofficial estimates run up to 2 million copies) confirm. At present the most successful distribution is run by FM Music Bank which has official outlets in Dar es Salaam and other main cities.

II Proud

Ni Mimi (1995) Recorded at Don Bosco Studio. Not in stores

Ndani ya Bongo (1997) Recorded at Master J. studio.

Distribution: FM Music Bank (East Africa only)

Niite Mr. 2 (1998) Recorded at Master J. studio. Distribution: FM Music Bank (East Africa only)

De-Plow-Matz

Tha De-Plow-Matz (1997) Recorded at Master J. studio and Soundcrafter studio. Distribution: FM Music Bank (East Africa only)

Kwanza Unit

Kwanza Unit (1994). Recorded at Mawingu studio. Not in stores

Run Tingz & Dedicated (1996). Recorded at Mawingu studio and Bongo House studio. Released on cassette by Bongo Records. Only 200 copies

Tropical Tekniqs (1995/6). Recorded at Soundcrafters studio. Released on cassette by Rumba-Kali (RAHH Records) in The Netherlands

G.W.M. (Gangsters With Matatizo)

Kipe Kitu (1996) recorded at Mawingu studio. Not in stores

Yamenikuta (1997) recorded at Mawingu studio. Not in stores

Saleh J

Ice ice baby: King of Swahili Rap (1991) Still available at shops in Dar es Salaam and Zanzibar. First Tanzanian rap album to be sold on a larger scale

Contish

Mabishoo (1994) Zanzibar group who recorded most songs live at Fuji Beach disco, Zanzibar Town. Still available at some shops all over Tanzania

W.W.A. (Weusi Wagumu Asilia)

Sauti ya Wagumu (1994) The first Kiswahili rap recorded in a studio (Don Bosco studio, Dar es Salaam)

Other artists whose tapes have been or still are available in the streets are: Mac Mooger, N.W.P. (Niggaz With Power), Ebony Moalim(Dar es Salaam), Kim Pekee, Da Struggling Islanders (Zanzibar), Rough Niggaz (Tanga), Jontwa Jokeri (Mwanza)

Books & articles

Gesthuizen, Thomas (1996). From Ice Ice Baby to Gangsters With Matatizo: hip hop in Tanzania (Dutch language). In: Baobab vol. 12, nr. 2 (September 1996). Leiden: Afrika-Stichting De Baobab

Maliyamkono, T.L. (1997). Tanzania on the Move. Dar es Salaam: TEMA Publishers

Rose, Tricia (1994). Black Noise: Rap music and black culture in contemporary America. Hanover: University Press of New England

Toop, David (1984). The Rap Attack: African Jive to New York Hip Hop. London: Pluto Press

Wallis, Roger and Malm, Krister (1984). Big Sounds from Small Peoples, the music industry in small countries. New York: Pendragon Press

Magazines and newspapers

Hip Hop Connection (September 1996). Music Maker Publications

The Express (July 31 – Augustus 6, 1997)

Dimba (August 10 – 16, 1997)

Lyrics: Sema nao

1998 by II Proud

From the album ‘Niite mr II’

Nasema nao

I talk to them

Nakwenda nao sambamba

I go with them side by side

Kwa mara nyingine tena niko ndani ya nyumba

Once again I am in the house

Mista II nakipa kitu kwa watu

Mister II representing to the people

Kama nilivyokipa kwenye ndani ya Bongo

Like the way I represented with ‘Ndani ya Bongo’

Na bado n’na usongo

And I am still strong

Napokuja ninakuja moja kwa moja

When I come I come straight

Kila mwaka mmoja mi nakuja na album moja nzito

Every single year I come with one strong album

Muziki wa geto

Music of the getto

Sauti yangu inafika mpaka Soweto

My voice goes up to Soweto

Nasema nao

I talk to them

Ma-mc wanabishana wao kwa wao nani zaidi

Mc’s argue amongst each other who’s the best

Yeyote awe zaidi mi nataka kitu kidogo

Anybody can be the best, what I want is money

Napiga ndogo-ndogo chini kwa chini

I do my things silently

Nipo makini na fani

I am careful in the game

Cheki ndani kuna nani na nani

Check who’s inside

Usikae kibubu-bubu taratibu anza kuhesabu

Don’t stay silently, slowly start to count

Moja mbili tatu

One two three

Mavitu ni yale-yale toka kwa mtu yule-yule

It’s just the same things from the same man

Nasema nao

I talk to them

Nakwenda nao kijela-jela

I go with them in a crazy way

Kila demu ninayemgusa analeta mambo ya hela

Every girl that I approach talks about money

Wakati mimi mwenyewe nataka hela

Meanwhile myself I want money

Oya msela – kubwa kuliko zote kwa Sindila

Oya msela – maximum respect to Sindila

Maisha ni vile unavyoishi

Life is how you live

Siku zinavyozidi na mi nazidi kuwa mbishi

As the days go by I keep on being die-hard

Shughuli ni watu na watu wenyewe ndiyo sisi

The party is people and the people is us

Wewe na mimi

You and me

Nani anasema na mimi mi nimkate kilimi-limi

Who is talking to me, I can make him shut up

Kila wakati nipo studio

Every time I am in the studio

Kila siku nasikika kwenye radio FM

Every day I am on the radio FM

Mademu wanaonifahamu wanionapo wanatabasamu

Girls who know me when they see me they smile

Choko – kama kichaa mi nna kichaa kuliko chako

Hoe – if you are crazy I am crazier than you

Na kama hujui kamwulize dadako kokote aliko

And if you don’t know go ask your sister wherever she is

Mi napiga zigzaga nigga

I make zig-zag nigger

Tiktaka mpaka ujione takataka

Tic-tac until you see yourself a fool

Mista II mi siyo fyatu ila tu mapepe mengi

Mister II I am not a fool, only hype

Bangi niliacha toka siku nyingi

It’s so many days since I stopped smoking all that bangi

Ukileta choko-choko mi naleta msukosuko

If you bring your shit I will bring trouble

Na sekeseke na sokomoko msela

And more trouble msela

Nilisema nao na bado nasema nao na ntasema nao

I talked to them and still i talk to them and I will talk to them

Nakutana na washikaji wa kila aina

I meet with different fellaz

Nakutana na mademu wa kila aina

I meet with different girls

Na nakutana na ma-mc wa kila namna

And I meet with different emceez

Cheki mmoja-mmoja cheki wawili-wawili

Check one by one, check two by two

Cheki watatu-watatu na bado tu mr II nasema nao

Check three by three, and still mr II I talk to them

Kwenye hip hop bado nipo-nipo nipo kila time

I am still in hip hop all the time

Kuna time nataka demu na kuna time sitaki demu

Sometimes I want a girl and sometimes I don’t want a girl

Nakuwa busy na business

I be busy with my business

Namna gani vipi? Yupi analeta zipi nimnanii kwenye nanino

What’s up? Who’s bringing shit, I will give him more shit

Toka tisini na tano mi natoa mfano

Since ninety five I give examples

Watu wanasema mi ni MC namba one

People say that I am the number one mc

Na mi nazidi kuwasha moto kwenye fani

And I am still setting fire in the game

Nenda kokote wakati wowote sema chochote kwa yoyote

Go wherever whenever say whatever to whomever

Mentali sijali nnachojali mi ni dili

I am crazy I don’t care I care about deals

Na dili ni dili bora ikubali ikikataa siyo zali

And a deal is a deal, if it works out and if it doesn’t it’s bad luck

Wacha kunitazama mtoto wa mama

Stop looking at me, mama’s boy

Hauna cha kusema kama mi nimesimama

You can’t talk when I am standing

Na nasema nao

And I talk to them

Footnotes

[1] In 1997, Thomas Gesthuizen was a student of African Studies at the University of Leiden and Peter Jan Haas was a student of Cultural Anthropology at the University of Amsterdam. Both were working on their thesis (MA) on Kiswahili rap.

[2] Most rap artists in Tanzania have English names. II Proud got his name before he was active as a rap-artist. He used to visit rap-concerts with an American friend of him. Everytime Joseph was boasting that he was better than the artists on stage. At one point his friend said: ‘Joseph, you’re just too proud!’. From this time on he was known as II Proud.

[3] The influence of commoditized music in East Africa goes at least back to the 1950’s when the urban areas experienced an influx of workers. According to Wallis and Malm (1984) in the Sixties Chubby Checker’s ‘Twist’ influenced the local music scene in Kenya. In the Sixties, Congolese music came to be the dominating form of pop throughout East Africa. (Wallis and Malm 1984: 32).

[4] Gesthuizen (1996). Also Remes, Pieter (1998). ‘Karibu ghetto langu – Welcome in my ghetto: Urban Youth, Language and Culture in 1990s Tanzania’. Ph. D. dissertation, Northwestern University, 1998.

[5] ‘Petty traders’. Many of them have recently migrated from upcountry to Dar es Salaam in search of a better future.

[6] ‘There are 11 dailies, 11 bi-weekly, 55 weeklies, 15 bi-monthlies and of all these 24 are in English and 68 in Kiswahili; 92 put together’ (page ix) in: T.L. Maliyamkono (1997).

[7] ‘Bongo’ is a local slang word referring to the city of Dar es Salaam or Tanzania (lit. ‘Brain’). The idea is that you need to have ‘brains’ to survive in Tanzania. Others explain that Dar es Salaam is the main town of Tanzania and seat of the government, thus it is the ‘brains’ of the country.

[8] Wallis and Malm (1984: 300).

[10] ‘Talking Point’, by John [21] Freestyling: the act of rapping without using pre-written lyrics. In American rap, freestyles originally were used by rappers in competitions, taking place on stage or just in the streets. In Tanzania, the challenge to battle is not heard very often. Freestyles are sometimes heard in informal gatherings, without the mc necessarily having an opponent. Sometimes the mc does use pre-written lyrics but in freestyle one is more free to change the sequence of the rhymes, thus creating a live atmospere which can be used to include ‘shout-outs’ and other references.

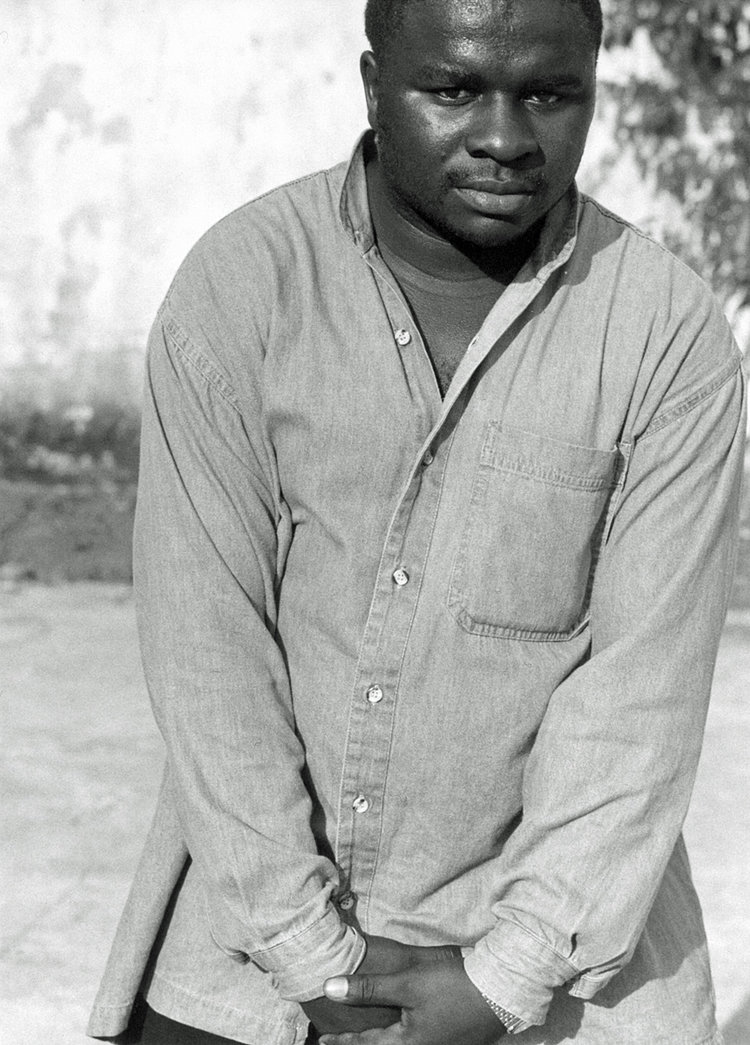

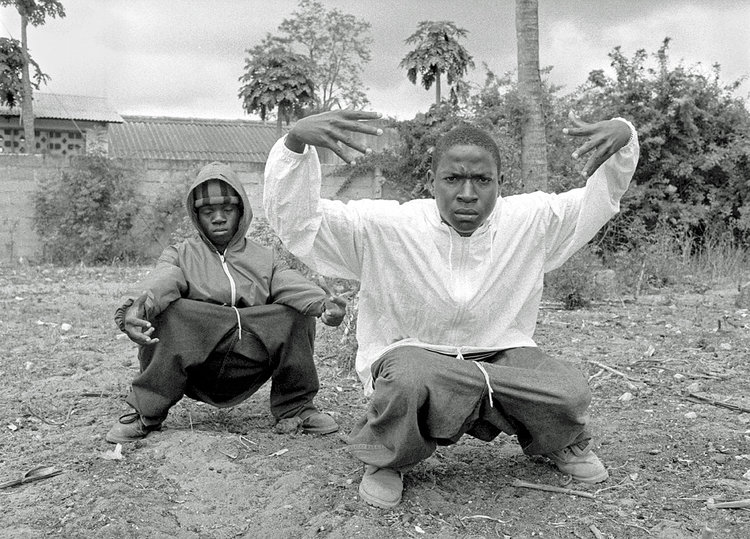

Photos: copyright Peter-Jan Haas

Samson Mwanjotile

February 10, 2012 (01:19)

I wish all the best to Mr II also known as Sugu, because he fought much on the way of saportig bongo hip hop music. So the big deal which can I insest to him is that ;Mr II as MP you have a good chance to fullfil your goals on HIP HOP REVOLUTION